Kendra Haste MRSS British, b. 1971

-

Overview'What interests me most about studying animals is identifying the spirit and character of the individual creatures. I try to create a sense of the living, breathing subject in a static 3-D form, attempting to convey the emotional essence without indulging in the sentimental or anthropomorphic.'KENDRA IS AN MA GRADUATE FROM THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF ART, LONDON

Working with the medium of galvanised wire, Kendra is established as a world-renowned contemporary animal sculptor. She is most well-known for the 2010 Historic Royal Palaces Commission to make thirteen sculptures for the Tower of London. 'Royal Beasts' helps tell the story of the Royal Menagerie that existed at the Tower from the 1200s. The works are permanently installed at this world heritage site.

Kendra is currently working towards a solo museum show in 2025 at the Ornamental Cast Iron Museum, Büdelsdorf, Germany. Ten new sculptures will act as an intervention highlighting sustainability, conservation and re-wilding.

Her work can be found in private collections and public institutions, including:National Museum of Wildlife Art, Wyoming

Tower of London

Cannon Hall Museum, Barnsley

London Underground at Waterloo Station, LondonStandard Chartered Bank, London.2017 - Elected to the Royal Society of Sculptors (MRSS)

2016 - Bison Head purchased by the National Museum of Wildlife Art, Jackson, Wyoming,

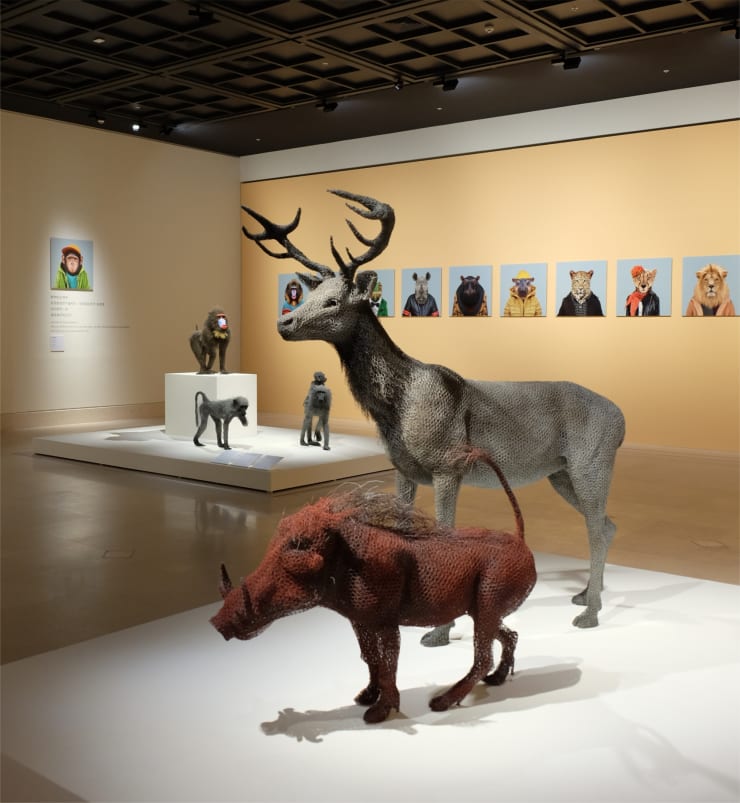

Let's Dance! Animals: Art and Design, Chimei Museum, Tainan, Taiwan

2015 - Elected to the Society of Animal Artists (USA)

2000 - Society of Wildlife Artists (UK)Available to commission with prices for work ranging from £5,000 - £65,000+.

-

Works

-

Hind, 2022

Hind, 2022 -

Bridget, 2022

Bridget, 2022 -

Barn Owl, 2023-24

Barn Owl, 2023-24 -

Bald Eagle, 2023

Bald Eagle, 2023 -

North American Red Fox, 2023

North American Red Fox, 2023 -

Racoon, 2023

Racoon, 2023 -

Nine Banded Armadillo, 2023

Nine Banded Armadillo, 2023 -

Antelope Jackrabbit, 2023

Antelope Jackrabbit, 2023 -

Young Baboon, 2023

Young Baboon, 2023 -

Red Stag, 2022

Red Stag, 2022 -

British Bulldog, 2014

British Bulldog, 2014 -

Boxing Hares

Boxing Hares -

Wild Mustang, 2021

Wild Mustang, 2021 -

Young Grizzly, 2020

Young Grizzly, 2020 -

Male Tiger Head (Relief), 2019

Male Tiger Head (Relief), 2019 -

Guinea Baboon, 2019

Guinea Baboon, 2019 -

Barn Owl, 2018

Barn Owl, 2018 -

African Buffalo Head, 2018

African Buffalo Head, 2018 -

Bison Head, 2016

Bison Head, 2016 -

Chacma Baboon Troop, 2017

Chacma Baboon Troop, 2017 -

Brown Bear (Grizzly), 2015

Brown Bear (Grizzly), 2015 -

Elephant (Relief), 2000-16

Elephant (Relief), 2000-16 -

Red Stag, 2015

Red Stag, 2015 -

Steller Sea Lion, 2015

Steller Sea Lion, 2015 -

Rhinoceros, 2000-14

Rhinoceros, 2000-14 -

Bottlenose Dolphin, 2014

Bottlenose Dolphin, 2014 -

Fallow Stag Head (Relief), 2011

Fallow Stag Head (Relief), 2011 -

Lioness Head (Study), 2011-19

Lioness Head (Study), 2011-19 -

Assyrian Winged Bull, 2004-06

Assyrian Winged Bull, 2004-06 -

Giraffe, 2004

Giraffe, 2004 -

Baboon Mother and Infant, 2003

Baboon Mother and Infant, 2003 -

Seated Cheetah, 2003

Seated Cheetah, 2003 -

Ostrich, 2003

Ostrich, 2003 -

Stalking Cheetah, 2003

Stalking Cheetah, 2003 -

Seated Male Baboon, 2003

Seated Male Baboon, 2003 -

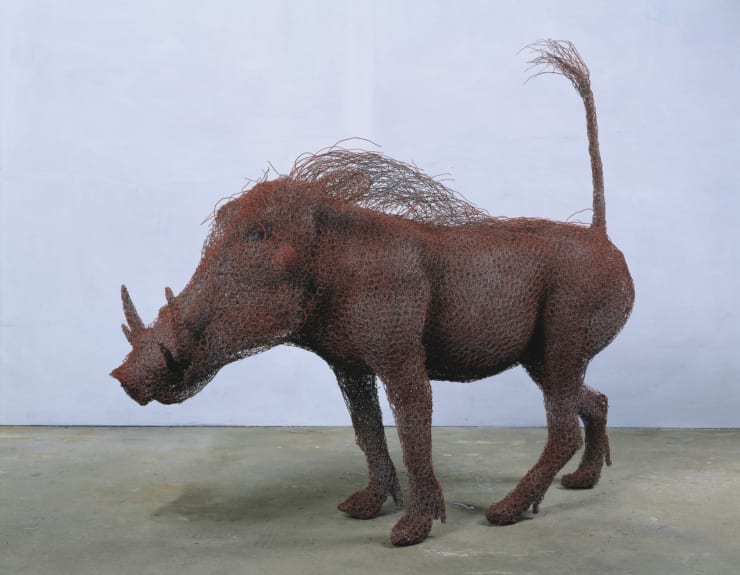

Warthog, 2002

Warthog, 2002 -

Timber Wolf, 2002

Timber Wolf, 2002 -

Walking Bengal Tiger, 2001

Walking Bengal Tiger, 2001 -

Hyaena, 2001

Hyaena, 2001 -

Mandrill, 2001

Mandrill, 2001

-

-

Statement

Animals have held an obsessive fascination for me throughout my life. Their diverse form, nature and behaviour provide a rich and inexhaustible depth of subject. Animals have been for many years and continue to be the sole focus of my work as a sculptor.The apparent ordinariness of wire and wire mesh belie their expressive potential and provide ideal material for my sculptures. Drawing is integral to my work as an artist and is perfectly matched by the linear qualities of wire. No other material I have ever used has been able to suggest the sense of movement and life, contour and volume, the contrasts of weight and lightness, solidity and transparency - values that I find in my natural subjects. It is the perfect medium, inviting continuing exploration and challenge.I have been privileged to study many of my subjects in the wild, extraordinary expeditions, whether tracking tigers in India or following wildebeest migrations through Tanzania. A direct and intimate study of animals is essential. I spend much time in zoos drawing the phenomena of anatomy and musculature; however, such analysis does not overwhelm my work, for it is the spirit and energy of the subject that I fundamentally seek to convey. My sculptures depict individual animals I have encountered, those I have spent time observing or who have left a deep impression on me. These are unique portraits rather than stereotypical, generalised interpretations of a species.I was raised in London, a childhood with few animals and little experience of wild places or even the countryside. Mine was very much an urban experience, separate from the natural world. My attraction to wild animals was born of the desire to connect with and discover something in their nature that was long ago lost within us. These preoccupations became obsessive and led me to study, in particular, the larger mammals and, of course, primates with whom we share so much - flesh, blood, muscle, and traits of behaviour. But, it is other unique aspects, the sense of another being, an individual spirit, inherent in each animal, that is the true subject of my work. -

Kendra In Conversation

Natalie Catren talks to Kendra Haste for Sculpture Review, published Winter 2018, vol LXVII.British wildlife sculptor Kendra Haste (b. 1971) always sculpts animals and always uses galvanized chicken wire mesh. Many of Haste’s works are virtual revisitations of prior historical displacements of the particular species discussed here. In this interview, Haste describes her technique from conception to completion and the intentions of her art.

NATALIE: WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO YOUR CURRENT CHOSEN MEDIUM (GALVANIZED WIRE/CHICKEN WIRE) AND TECHNIQUE?Kendra: Galvanized wire mesh is traditionally used as an armature material under clay or other material. I always liked the aesthetic of the wire form at this stage. Drawing is an important part of my work, and it is the linear quality of wire that I find so aesthetically appealing. My first sculptures were made using wire mesh for a troop of life-size chimpanzees inspired by the chimps at the London Zoo. The mesh assimilated the cross-hatching techniques in drawing and was an exploration of drawing three-dimensionally in space.

NATALIE: WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES INHERENT TO THIS MEDIUM?

Kendra: The challenge when using wire mesh and sculpting in layers is to keep the wire expressive by not overworking it into something overly dense, lifeless, and lumpen. Also, sourcing a superior quality, heavily galvanized steel hexagonal mesh is proving an increasingly tricky challenge, and I've had to have my wire specifically manufactured in Belgium.

NATALIE: WHAT, FOR YOU, ARE THE STRENGTHS AND SHORTCOMINGS OF THE MEDIUM?

Kendra: The strengths of this medium are that it is easily accessible, only needing wire, snips, and pliers to manipulate into shape, and if errors are made, they are easily corrected by cutting out or adding, much like drawing. Wire is an incredibly versatile material and can take on many textures, shapes, and tones. I find cast metal and bronze sculptures cold and heavy to empathize with the animal form, which can have a deadening effect. The fact that the mesh has holes and there is no solid surface, even when worked more densely, adds a sense of vitality and life to the sculptures. The layers of wire depicting the bone and muscle can be sensed beneath the final skin, hair, and surface detail. For such a heavily processed material, the mesh is sympathetic and works well in creating organic forms. The main shortcoming of the medium, other than being harsh on my hands, is the length of time it can take to create a sculpture. With each sculpture being built up in layers and sewn in with binding wire, it is an incredibly time-consuming, slow process, although very rewarding.

NATALIE: CAN YOU DESCRIBE YOUR WORKING TECHNIQUE, FROM CONCEPTION TO FINISH?

Kendra: I start by doing many quick observational drawings of my animal subject, ideally in the wild, but if not, at zoos. I observe animal behaviour and form, researching in museums, referencing photos and video. Some sculptures have welded mild steel frames inside, depending on scale and where the sculpture is to be displayed and fixed, but smaller pieces are often built up with just the wire. After researching my subject, I have a good idea of my starting point. I begin with the spine line and create a rough skeletal form and stance, although this can often change as I make it. The material often suggesting a change of flow. I work from the inside out, so from the skeletal shape, I add the rough muscle shapes in layers sewn into the mesh with a binding wire adding layer upon layer to the final skins and texture. I like to draw the animal out as I sculpt it, making large charcoal drawings, which feed back into the sculptures and help work through the challenges of the process.

NATALIE: WHO ARE OR HAVE BEEN YOUR BIGGEST INFLUENCES, ARTISTIC OR OTHERWISE?

Kendra: I love looking at the ancient Assyrian wall reliefs in the British Museum. The animals are so beautifully observed and exquisitely executed. I also love the explorative, inquisitive observational animal drawings of the Renaissance artists such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Pisanello, and Durer. George Stubbs, the famous English horse painter of the eighteenth century, depicted animals with such authenticity. His anatomical drawings are masterpieces in their own right and helpful references in the studio. Contemporary artists I admire are Elisabeth Frink, whose sculpture has a powerful physicality and presence, and the sculptor Nicola Hicks who manages to breathe life into her bronzes through her expressive, captivating plaster and straw sculptures.

NATALIE: CAN YOU DESCRIBE AND DISCUSS YOUR FAVORITE ARTIST'S TOOLS?

Kendra: My favorite tools are my small needle-nosed pliers, which are an extension of my fingers, and I use them to weave the mesh together, and my wooden hammer, whose head gets worn and smaller year after year.

NATALIE: WHAT BROUGHT YOU TO ANIMALS AS PORTRAIT SUBJECTS? CAN YOU TALK A BIT ABOUT YOUR THESIS - "THE ROLE OF ZOOS," AS YOU SAID IN YOUR VIDEO INTERVIEW?

Kendra: Animals fascinate me and have always been my primary source of interest and inspiration. While at college, I wrote a thesis on the changing role of zoos and how they reflect our complex relationship toward the natural world. From historic wild animal collections, such as the Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London, which once were curiosities and symbols of power and status, to today's modern "good" zoos that promote the conservation of endangered species through captive breeding programs and research.

NATALIE: DO YOU USE LIVE MODELS? IF YES, THEN HOW AND WHERE? IF NO, HOW DO YOU COMPOSE?

Kendra: I have been lucky enough to be involved in expeditions to India and East Africa and have spent time observing wildlife in their natural habitats. I also rely on zoos for close observational drawing. I also use photographic and video images in researching my animal subjects.

NATALIE: DO YOU HAVE A SPECIAL AFFINITY FOR CHACMA BABOONS? YOU'VE SCULPTED A LOT OF THEM.

Kendra: I find the larger primates the most interesting animals to study, as they are so like us. I first encountered wild baboons in Tanzania, East Africa. They were Olive baboons, and their vast troops numbered 100+. Much time was spent sketching and observing the troop; their strong individual characters and energetic natures made them fascinating to study. The alpha males, in particular, have a great swagger and bold attitude, they are fiercely intelligent and inquisitive, and their wonderful form, the doglike muzzle, muscularity, and spiky hair reflect anarchic natures. Chacma baboons have been a popular choice of commission as they work well in a domestic setting, as they are often seen in South Africa in both the wild and urban environments brazenly raiding gardens and climbing up buildings. This species epitomises the conflict between our ever-growing populations and the resulting pressures on the natural world.

NATALIE: WHAT MAKES YOU CHOOSE TO USE OR NOT USE COLOR? HOW DO YOU THINK ABOUT COLOR IN YOUR WORK?

Kendra: I mainly use monochrome metallic paint to add tone to my sculptures. I do not want colour to be a distracting surface pattern and only use it where it is integral to the animal form and character. I have used it, for example, on the mandrill, which is all about colour and display, and warthogs, as I witnessed them in the wild, bright red from rolling in Tanzanian soil.

NATALIE: HOW OFTEN ARE YOUR ANIMALS SPECIFICALLY COMMISSIONED, AND HOW OFTEN DO YOU CHOOSE WHAT ANIMAL SUBJECT GOES WHERE? DO PATRONS GENERALLY HAVE A CERTAIN PERCEIVED RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ANIMAL COMMISSIONED? DO YOU? OR DOES THE PLACE?

Kendra: Some clients are very specific about the animal subject they want portrayed, but I have been very fortunate to have a great deal of freedom with commissioned work. I visit and view the proposed site internally or externally, then draw up ideas to work through with the client. For example, the life-size giraffe in the stairwell began as a concept of birds suspended in the space, but the site suggested something more substantial from the base up, and the giraffe was realized and resulted in a successful site-specific piece.

NATALIE: THE ELEPHANT AT WATERLOO JUBILEE LINE: HOW WAS IT COMMISSIONED? WAS THE ELEPHANT YOUR CHOICE? WHY AN ELEPHANT? CAN YOU DISCUSS ITS PARTICULAR PLACEMENT AND CONCEPTION? WHAT WAS INVOLVED IN THE PROCESS OF CLEANING? AND REFURBISHMENT?

Kendra: The elephant that resides at Waterloo station was initially made for an exhibition at Gloucester Road tube station on a disused platform. It was called "Urban Safari", and I created five life-size sculptures: the elephant, rhino, oryx, giraffe, and vulture emerging from the walls of the arches on the platform. When London Underground bought the Elephant, they planned to place it at Elephant & Castle tube station, but the ceilings proved too low! Waterloo station proved a perfect home and even has a historical connection, as adjacent to the station was Astley's Amphitheatre, where famously, in 1828, a frightened elephant escaped and rampaged through the London crowds. I enjoy the juxtaposition of the busy urban commuters with this ghostlike giant of the wild, a reminder of the power of nature towering over us but also of its fragility in survival. As the Elephant was initially made for a temporary exhibition at Gloucester Road, it needed a steel frame inserted internally to display it in the long term. After a few years displayed on such a busy site, the wire had become very dirty, so it was industrially hoovered and then reworked by adding a fresh skin of wire and a re-spray.

NATALIE: HOW DO YOUR MEDIA COPE WITH WEATHER, POLLUTION, AND THE ELEMENTS GENERALLY?

Kendra: The quality of the wire and the galvanizing paint ensure that the sculptures survive well outside in the elements. If needed, the recoating of a galvanizing paint every few years can be applied to prevent corrosion.

NATALIE: YOUR RHINO (2000-2014) IS EMERGING LIKE THE JUBILEE LINE ELEPHANT OUT OF THE WALL. WHEN DID YOU FIRST USE THIS AS A DEVICE? WHAT IS ITS SIGNIFICANCE FOR YOU? IN OTHER WORDS: HOW MIGHT YOU DESCRIBE YOUR ARTISTIC RELATIONSHIP TO THE WALL?

Kendra: The Rhino was originally conceived with the Elephant for the "Urban Safari" exhibition. I was inspired to use the walls of the architecture and arches at Gloucester Road tube station. I enjoy using walls as a dimension of the artistic aesthetic, and I have created many wall-fixed reliefs where it directly corresponds to drawing with wire.

NATALIE: WHAT INFLUENCED THE POSES AND PLACEMENT OF YOUR TOWER OF LONDON LIONS?

Kendra: Although the Barbary lions that would have been kept at the Tower were likely to have been in poor health and malnourished, I wanted to convey their strong, powerful, and physical presence in the medieval confines of the Tower. They would have been an intimidating presence to visitors at the Tower, and I wanted my sculptures to recreate this uneasy feeling by placing the lions in a stalking stance, with the male lion's eyes focusing in on today's visitors as they queue at the entrance gate.

NATALIE: DO YOU EVER THINK IN TERMS OF MASKS AND MASKING? I'M THINKING OF THE BABOON IN THE CHIMEI MUSEUM EXHIBIT, AND YOUR HEADS EMERGING FROM WALLS-LIKE HUNTER'S TROPHIES, YES, BUT ALSO LIKE MASKS.

Kendra: My animal heads can have something of a mask-like quality. I have a small collection of masks from my travels and enjoy their aesthetic, which has subconsciously fed into the creative process!

NATALIE: CAN YOU TALK ABOUT YOUR WORK IN TERMS OF TRANSPARENCY, VEILING, FADING, OR INCORPOREALITY, BOTH SYMBOLICALLY AND IN TERMS OF TECHNIQUE? THE FINAL PHOTOGRAPH OF YOU WORKING ON THE JUBILEE LINE ELEPHANT MADE ME THINK OF THIS, AND THEN IN YOUR VIDEO INTERVIEW, YOU SAID THAT THE CHICKEN WIRE GIVES YOUR ANIMALS THE "SENSE OF GHOSTLIKE CREATURES OF THE PAST."

Kendra: The wire definitely evokes an ethereal quality to the sculptures, which can be used to greater or lesser effect depending on how much wire is used. But even the more robust, solid sculptures at the Tower of London have a ghostlike presence, partly because of their monochrome colour but also because the wire is ambiguous at certain distances and can emit ephemeral qualities. These values of the wire also lend themselves symbolically to depicting endangered wildlife whose very survival hangs in the balance and could sadly become creatures of the past.

NATALIE: HOW DO YOU DEFINE "ANTHROPOMORPHIC"? DO YOU FEEL THE MEANING OR CONNOTATION OF THE WORD HAS CHANGED IN THE LAST TWENTY YEARS?

Kendra: I want to avoid overly sentimental anthropomorphism in my work as it can be detrimental to the truthful depiction of wild animals and detracts from the seriousness of wildlife as a subject. I think the connotation of the word "anthropomorphic" has changed in the last twenty years. In science, thanks to zoologists like Jane Goodall and other animal behaviorists, we understand that animals are highly emotive beings and share more with us than previously thought. My objective is to ultimately create naturalistic, authentically observed portraits of animals and attempt to capture something of our fellow creatures' essence, energy, and majesty.

NATALIE CATREN is a free-range freelance writer based in the UK. Equally uncomfortable on either side of the Atlantic, she hopes one day to live in a lighthouse. -

-

-

CREATING THE ROYAL BEASTS AT THE TOWER - KENDRA TALKS ABOUT THE HISTORIC ROYAL PALACES COMMISSIONAs an art student, while researching the history of London Zoo, I discovered the existence of the Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London, which formed the nucleus of the Zoo’s original animal collection in the 1830s. Later at the Royal College of Art, working on my thesis about the changing roles animals played in the visual arts, I came across some of the early engravings and prints of the Tower’s menagerie animals in the Royal Armouries collection. I am an animal artist who relies on zoos for direct observation and close study of my subjects. I have long been interested in our complex, changing relationship with wildlife and animals in captivity. So, when learning of the proposed ‘Royal Beasts’ exhibition and sculpture commission at the Tower through my art dealer, Patrick Davies, we were very keen to submit a proposal.To visually communicate the story of the menagerie that existed for hundreds of years at the Tower to the vast number of visitors was a challenging concept for the Historic Royal Palaces Interpretation team. Short of confining live animals for display, how else could the atmosphere and bizarre juxtaposition of wild animals be created in the Towers’ confined surroundings. The team also wanted to avoid cheapening such an important historical story by using animal replicas, more suited to a theme park: the physical presence and sculptural material would be the key. Fortunately, my principal medium of wire matched perfectly. The linear qualities of wire paralleled the expressive qualities of the beautiful animal drawings and engravings in the Royal Armouries collection, some of which would form part of the exhibition. The wire sculptures look very different in changing light and at different distances can create an ephemeral, ethereal quality to the image. The monotoned, shadowy forms help add to the sense of these ‘ghost creatures’ from the past. In addition, the fencing mesh used, a material often used in confining animals, helps to reflect the idea of captivity.

CREATING THE ROYAL BEASTS AT THE TOWER - KENDRA TALKS ABOUT THE HISTORIC ROYAL PALACES COMMISSIONAs an art student, while researching the history of London Zoo, I discovered the existence of the Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London, which formed the nucleus of the Zoo’s original animal collection in the 1830s. Later at the Royal College of Art, working on my thesis about the changing roles animals played in the visual arts, I came across some of the early engravings and prints of the Tower’s menagerie animals in the Royal Armouries collection. I am an animal artist who relies on zoos for direct observation and close study of my subjects. I have long been interested in our complex, changing relationship with wildlife and animals in captivity. So, when learning of the proposed ‘Royal Beasts’ exhibition and sculpture commission at the Tower through my art dealer, Patrick Davies, we were very keen to submit a proposal.To visually communicate the story of the menagerie that existed for hundreds of years at the Tower to the vast number of visitors was a challenging concept for the Historic Royal Palaces Interpretation team. Short of confining live animals for display, how else could the atmosphere and bizarre juxtaposition of wild animals be created in the Towers’ confined surroundings. The team also wanted to avoid cheapening such an important historical story by using animal replicas, more suited to a theme park: the physical presence and sculptural material would be the key. Fortunately, my principal medium of wire matched perfectly. The linear qualities of wire paralleled the expressive qualities of the beautiful animal drawings and engravings in the Royal Armouries collection, some of which would form part of the exhibition. The wire sculptures look very different in changing light and at different distances can create an ephemeral, ethereal quality to the image. The monotoned, shadowy forms help add to the sense of these ‘ghost creatures’ from the past. In addition, the fencing mesh used, a material often used in confining animals, helps to reflect the idea of captivity.

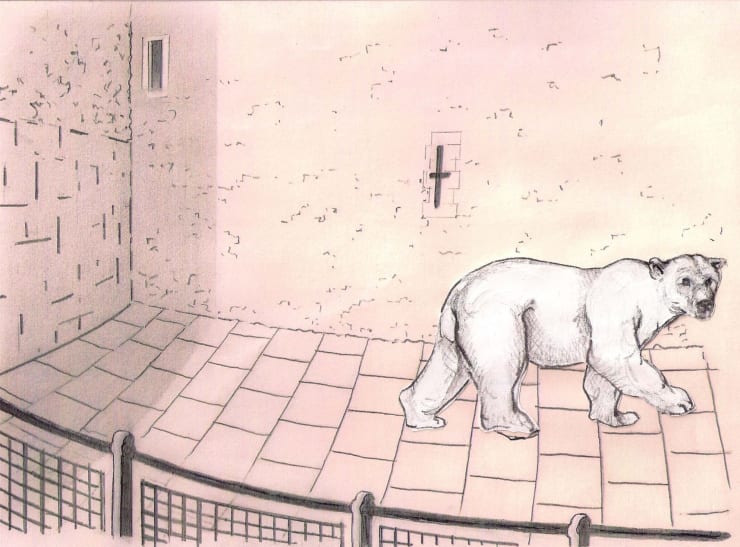

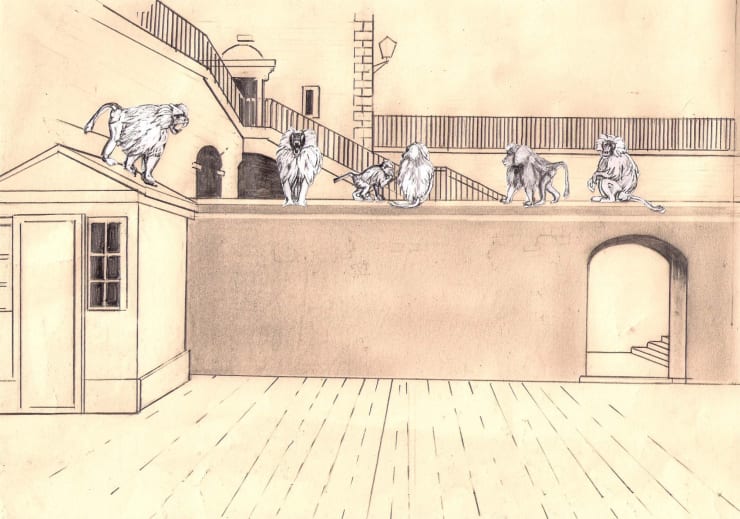

The original Polar bear was a gift from the King of Norway to Henry III in 1251, making this Artic animal's first appearance in England. The African elephant was also a gift to Henry III by the King of France, and again this was the first ever seen in England and caused much excitement on its journey from Dover to the Tower. The King had a unique wooden house made for the elephant, but it sadly died two years later and, given how little was then known of its natural diet, had been given red wine to drink. Monkeys were always a popular menagerie attraction, and in the 1750s, visitors to the Tower experienced ‘The School of Monkeys' who were allowed to roam free in and around the visitors. Records exist of a particularly violent baboon who used to smoke a pipe and hurl objects and stones at the visitors; even on its journey to the Tower, this animal reportedly killed a boy by throwing a cannonball at him. I wanted to echo this anarchic sense of unruly energy by having the baboons interacting with each other as a wild troop, sitting on the walls and up on one of the Tower’s turrets. The placing of the selected animals within the Tower also had to be historically relevant. The Tower is a Listed Monument and a World Heritage Site, and English Heritage had to follow strict criteria and regulations in placing and fixing the sculptures. The three wire lions were placed on top of the old Lion Tower to have an obvious location connection. At the same time, the Polar Bear is situated where the river embankment would have been in the 13th century and feasibly where the bear was allowed to fish in the Thames attached to a long chain. The wooden elephant house, although no longer in existence, was considered most likely to have been in the Inner Word area near the White Tower, so we chose the archway opposite to help create a sense of claustrophobic confinement. The fixings to make these life-size, steel-framed, heavily wired sculptures safe and secure and not damage the ancient listed surfaces proved a particular challenge. Thankfully, the expertise of the art installer James Shearer’s ingenious technical and design solutions made the whole installation possible.

Working with a small team of assistants, the wire menagerie of thirteen sculptures took a year and a half to complete. I wanted the pieces to portray the mighty, physical presence of the ‘Royal Beasts’ in their incongruous surroundings at the Tower. These were very much wild animals, viewed as aliens and curiosities, unseen by the population before and looked after by guardians with little or no understanding of animal welfare, which sadly resulted in many of these creatures having short, cruel lives. Today’s public relates to the ‘Royal Beasts’ and their history from a more empathetic and knowledgeable viewpoint in stark contrast to the visitors of the menagerie centuries before. I trust my sculptures represent something of the ‘live animals’ and help resonate the ‘beasts’ predicament and their emotive being and powerful physicality within the confines of the fortress. A haunting glimpse of the former animal inmates, an uncomfortable reality adding to the richness of the past and another macabre, intriguing story in the fascinating history of the Tower of London. -

KENDRA AND SALLY DIXON-SMITH, CURATOR (COLLECTIONS) H M TOWER OF LONDON AND BANQUETING HOUSE WHITEHALL, DISCUSS THE ROYAL BEASTS PROJECT AT THE TOWER OF LONDON - 2012

-

THE ROYALS (S1 E6 - ROYAL PETS) CHANNEL 5 DOCUMENTARY (2016)

-

-

-

-

-

Film

-

African Buffalo Head

Private client commission (2018) -

Barn Owl

Private client commission (2018) -

Baboon Mother and Infant

Private Collection. Exhibited at the Chimei Museum, Tainan, Taiwan in 2016. -

Young Grizzly

Private client commission (2020) -

Guinea Baboon

Private client commission (2019) -

Chimei Museum

Let's Dance! Animals: Art And Design, Chimei Museum, Tainan, Taiwan, 2016 Exhibiting in Asia for the first time, five of Kendra's sculptures were included in a museum show dedicated to... -

Royal Pets

2016 Channel 5 Televison Documenary Series The Royals (S1 E6 - Royal Pets) Kendra discusses her 2011 commission for Historic Royal Palaces at the Tower of London. -

Tower of London

Kendra Haste and Sally Dixon-Smith, Curator (Collections) H M Tower of London and Banqueting House Whitehall, discuss the Royal Beasts project at the Tower of London 2012

-